Leading Through Crisis: Healthcare Supervisor Resilience

Building leadership capacity for the next healthcare emergency.

In This Article

Lessons Forged in Crisis

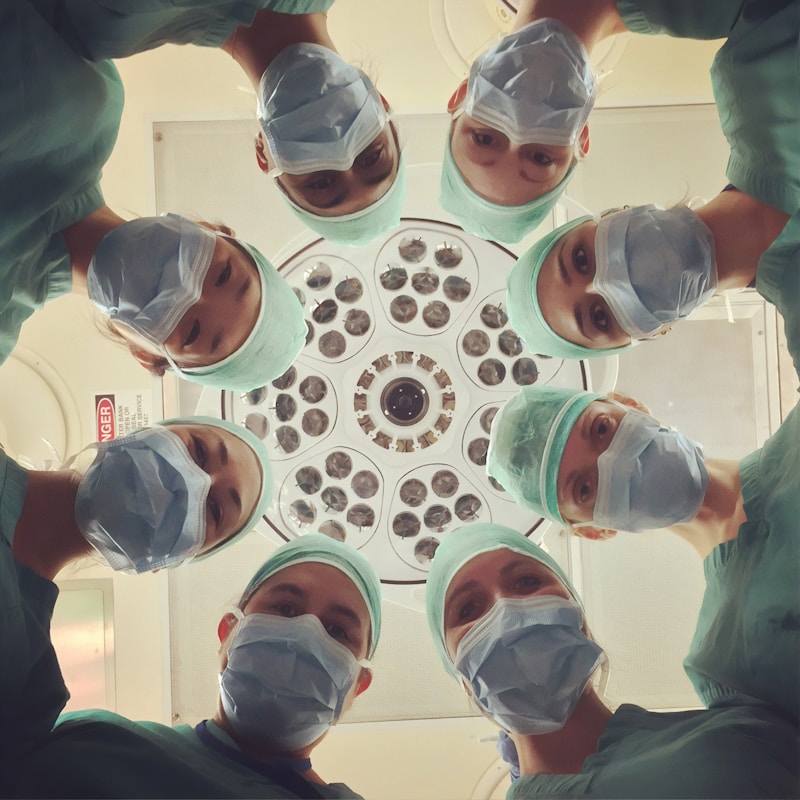

Healthcare has always demanded resilience from its leaders. But the intensity and duration of recent crises, from pandemic surges to staffing emergencies, have tested supervisors in ways that no leadership training program could fully prepare them for. The leaders who emerged from these experiences carry hard-won insights about sustaining themselves and their teams through prolonged adversity.

These lessons are not theoretical. They come from charge nurses who managed units running at 150% capacity, department supervisors who rebuilt teams after mass resignations, and clinic managers who maintained care quality while navigating supply shortages and rapidly changing protocols.

The Marathon Mindset

The most critical lesson from recent healthcare crises is the difference between sprint and marathon leadership, a concept often discussed in leadership and crisis management literature. Early in any crisis, adrenaline and purpose carry teams forward. People work extra shifts, skip breaks, and push through exhaustion because the urgency feels temporary. "We just need to get through this week" becomes the rallying cry.

But when the crisis extends for weeks, then months, then years, the sprint mentality becomes destructive. Leaders who maintained their team's capacity over extended periods made a deliberate shift:

- Acknowledging duration honestly rather than repeatedly promising that relief was coming soon

- Enforcing recovery even when it felt counterintuitive to send people home during staffing shortages

- Normalizing struggle by openly discussing fatigue, frustration, and grief rather than maintaining a relentless positivity facade

- Adjusting standards to reflect crisis reality without abandoning professional commitment

Emotional Leadership Under Pressure

Healthcare supervisors in crisis settings function as emotional shock absorbers for their teams. They absorb anxiety from above (administration decisions, resource constraints) and distress from below (patient suffering, team exhaustion) while maintaining enough composure to make sound decisions.

This emotional labor is often invisible and rarely acknowledged in formal leadership assessments. Yet it may be the most critical competency a healthcare supervisor possesses.

Sustainable emotional leadership practices

- Structured check-ins that go beyond "how are you doing?" to specific questions: "What is keeping you up at night?" or "What do you need that you are not getting?"

- Permission to grieve publicly. When a supervisor says "Today was terrible, and it is okay to feel that way," it validates the team's experience

- Boundary setting around exposure to traumatic content during off hours, including limiting news consumption and social media engagement

- Peer support networks among supervisors who can share experiences without the power dynamics that complicate team conversations

Decision-Making in Uncertainty

Crisis conditions force leaders to make high-stakes decisions with incomplete information. Healthcare supervisors during recent crises faced choices that would have seemed unthinkable in normal operations: how to allocate scarce resources, which protocols to modify, when to deviate from standard practice.

The leaders who navigated this well developed a framework:

Triage the Decision

Not every decision in a crisis requires deep deliberation. Effective leaders quickly categorize:

- Reversible decisions that can be made quickly and adjusted: staffing assignments, supply allocation, workflow modifications

- Irreversible decisions that require more careful consideration despite time pressure: scope of practice changes, patient care protocol modifications, team restructuring

- Decisions to defer that seem urgent but can actually wait for better information

Communicate the Reasoning

Teams accept difficult decisions more readily when they understand the logic behind them. Even when the decision is unpopular, transparency about the constraints and trade-offs builds trust. "I know this is not ideal, but here is why we are doing it this way" is vastly more effective than "this is what we are doing."

Accept Imperfection

Crisis decisions are inherently imperfect. Leaders who wait for the perfect solution while conditions deteriorate cause more harm than those who make reasonable decisions and adjust as new information arrives.

Rebuilding After Crisis

When the acute phase of a crisis passes, healthcare supervisors face a different challenge: rebuilding teams that may be depleted, demoralized, and fundamentally changed by their experiences.

Recovery priorities:- Acknowledge what happened through structured debriefs that honor both the hardship and the achievements of the crisis period- Address staffing gaps thoughtfully, recognizing that rapid hiring without adequate onboarding creates new problems

- Restore normal routines gradually, giving teams time to readjust to non-crisis expectations

- Identify lasting changes that should be kept versus crisis adaptations that should be retired

- Support individual recovery through employee assistance programs, flexible scheduling, and genuine attention to work-life balance

Building Resilience Before the Next Crisis

The most valuable outcome of crisis experience is the opportunity to prepare for what comes next. Healthcare supervisors who have lived through prolonged crises understand preparation differently than those who have only trained theoretically.

Pre-crisis investments that pay dividends

- Cross-training depth: Teams that can only function with specific individuals in specific roles are fragile. Building genuine cross-training so that multiple team members can competently perform critical functions creates the flexibility crisis response requires.

- Communication infrastructure: Crisis communication needs are predictable even if the specific crisis is not. Establishing channels, cadences, and escalation protocols before they are needed saves critical time when they are.

- Relationship banking: Supervisors who invest in strong relationships with their teams during normal operations have a reserve of trust and goodwill to draw upon during difficult periods. Crisis is not the time to start building trust.

- Personal resilience practices: Leaders cannot sustain their teams if they cannot sustain themselves. Establishing genuine self-care practices, professional boundaries, and support networks before crisis hits is not optional.

The Frontline Take

Healthcare crisis leadership is not about heroics. It is about sustainability. The supervisors who protect their teams most effectively during prolonged adversity are not the ones who push hardest. They are the ones who pace wisely, communicate honestly, make imperfect decisions with confidence, and invest in recovery as deliberately as they invest in response. These are skills that can be developed, and they must be developed before the next crisis arrives, not during it.

Key Takeaway

Building leadership capacity for the next healthcare emergency.

Frontline Take

HR's View From The Floor

Related Articles

New Opportunities, New Risks: Using AI to Engage Healthcare Teams Across Shifts and Schedules

Healthcare organizations are turning to AI-powered tools to bridge communication gaps across 24/7 operations—but implementation requires careful attention to burnout, equity, and trust.

Nurse Manager Burnout: Recognition and Recovery Strategies

Supporting the leaders who support patient care.

Patient Experience Starts with Staff Experience

Why investing in frontline healthcare workers improves patient outcomes.